Seoul, Korea, was a feast for my senses during my recent trip from May 14th to May 28th.

This wasn’t my usual visit, though. This time, my focus wasn’t on the architecture. Instead, I indulged in eating, shopping, and walking very slowly (due to my mom’s leg pain).

Despite the culinary adventures, I couldn’t ignore the buzz about the Dongdaemun Design Plaza (DDP) by the legendary architect Zaha Hadid, completed in 2014.

Curiosity got the best of me, and after two days of food-filled bliss, I decided to venture out to the Dongdaemun area to check out the outstanding structure.

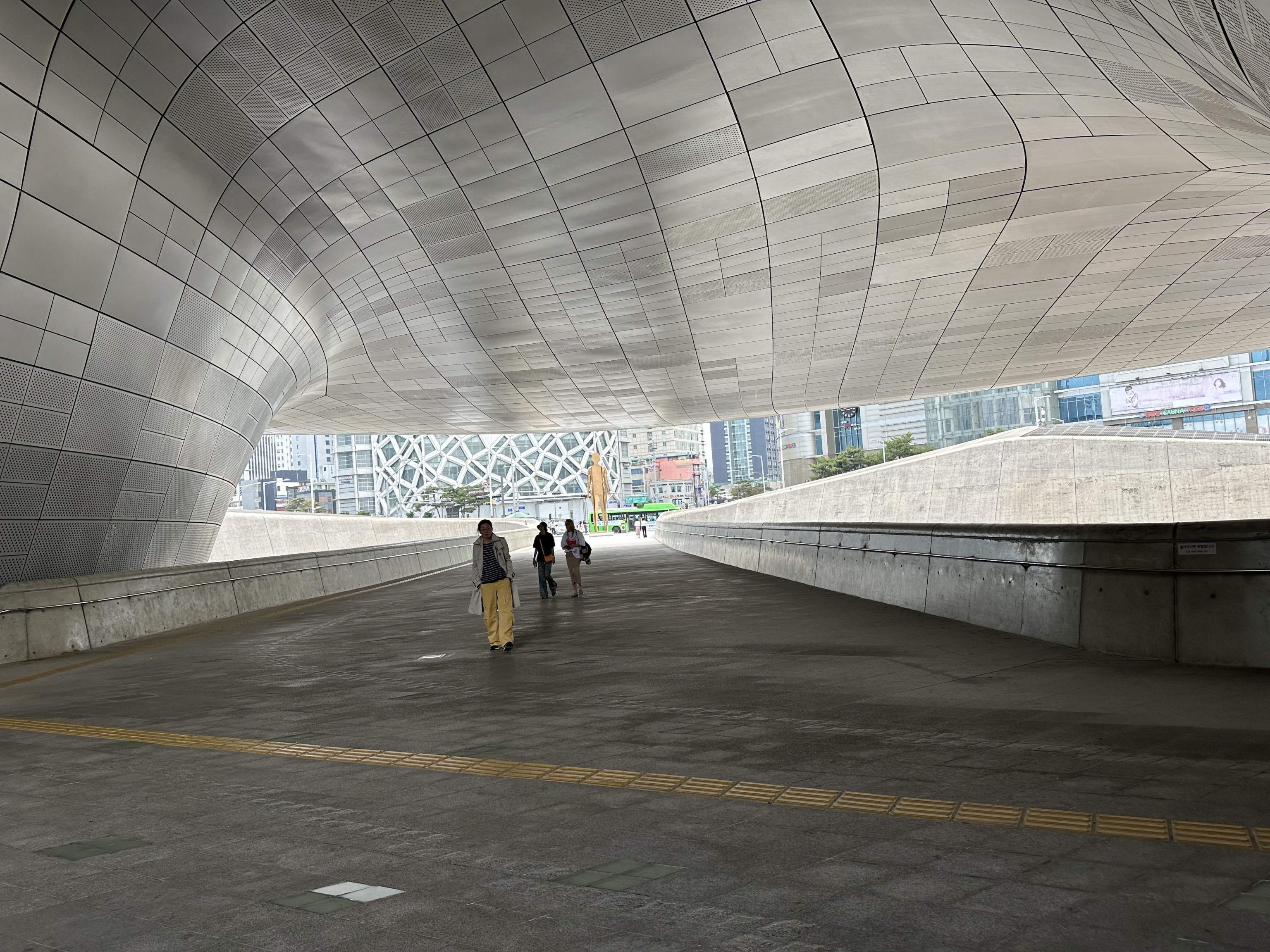

Exiting the subway, I was immediately confronted by the gigantic, futuristic structure that starkly contrasted with the historical backdrop of Seoul.

Naturally, I signed up for a tour to check out the story behind this project and the competition that led to its creation. But first, lunch—because priorities:-)

Background of the DDP Competition

Seoul had grand ambitions to position itself as a global design hub, a vision strongly championed by its mayor at the time.

The competition to design the DDP was a critical part of this ambition.

The site, an uncelebrated historical area previously home to an old baseball stadium with ties to Korea’s oppressive Japanese occupation, was set for a transformation.

The competition directives were clear and future focused-thinking:

- Develop creative and future-oriented design.

- Establish a strategic base for the design industry.

- Create a global design knowledge exchange system.

- Build a designer network platform.

- Serve as a hub for cultural and art activities.

- Become a global landmark to boost tourism.

- Foster a creative environment and place identity.

- Promote downtown trading area progress.

Eight architects, including four from Korea and four international contenders, were invited to participate. Among them was Zaha Hadid, whose design ultimately won.

Her concept, known as a “Metonymic Landscape,” emphasized the movement of people and integration with the surrounding area rather than focusing on the historical identity of the site.

The project was intended to be a “catalyst” for Seoul’s vision of a futuristic, creative design city, and it succeeded in this mission.

According to the article written Hyon Sob Kim, the competition materials scarcely mentioned the historical significance of the old stadium or its earlier ties to Japan, which brings us to an important point: blaming the architect for not incorporating historical aspects is misplaced.

The DDP competition was more than just a call for innovative design—it was a statement of intent.

Seoul’s leadership wanted to leap into the future, shedding the weight of the past and embracing a new identity as a global design leader.

This vision was encapsulated in the competition’s eight directives, each aimed at fostering creativity, enhancing the design industry, and boosting tourism.

The site for the DDP, an old baseball stadium with a less-than-celebrated history, was a blank canvas ripe for transformation.

The competition attracted top talent, including four Korean and four international architects.

Zaha Hadid’s winning design stood out because it embodied the essence of movement and connectivity, creating a dynamic space that resonated with Seoul’s aspirations.

Her “Metonymic Landscape” concept was a perfect fit for a city looking to position itself as a forward-thinking, innovative hub.

Past vs. Future: What is more important?

Seoul’s emphasis on a futuristic vision was mirrored perfectly in Hadid’s design.

The city was less concerned with the past and more focused on what the DDP could symbolize for its future.

The aim was to create a Bilbao Effect, akin to Frank Gehry’s transformative Bilbao Museum, which revitalized the city and turned it into a tourist hotspot.

With a relatively modest(?) budget of $350 million and a swift construction timeline of five years, the project also underscored the importance of tourism.

Today, DDP is a bustling hub where Korean fashion shows and celebrities draw countless locals and tourists, achieving the city’s goal of a design and tourism epicentre.

The decision to prioritize the future over the past in the DDP project is reflective of a broader trend in urban development.

Cities worldwide strive to reinvent themselves, using iconic architecture as a catalyst for change and growth.

The Bilbao Effect, named after Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, is a prime example.

This phenomenon describes how a single landmark can revitalize a city’s economy and global image. Seoul aimed for a similar(if not the same) outcome with the DDP.

The city allocated $350 million to the project, a significant yet relatively modest investment for such a grand vision. The five-year construction timeline was ambitious, reflecting the Korean cultural emphasis on speed and efficiency.

The success of DDP as a tourism magnet is evident today.

Fashion shows, celebrity events, and the steady stream of visitors snapping photos and videos attest to its impact.

The DDP has not only met but exceeded the objectives set out in the competition directives, becoming a symbol of Seoul’s transformation into a global design hub.

Money Rules

Walking through the DDP, I couldn’t help but notice how the design hub and tourism objectives had seamlessly come to life.

Everywhere I looked, there were people—both Koreans and foreigners—capturing the essence of this futuristic structure with their cameras and smartphones.

The DDP wasn’t just a structure; it was a thriving social media backdrop, a hotspot for fashion shows, and a magnet for celebrity events.

This got me thinking about the real driving force behind its success: money.

Seoul’s ambition to replicate the Bilbao Effect with the DDP was not just about aesthetics; it was a strategic economic move.

The city allocated a budget of $350 million for the project, which, in the grand scheme of global architectural landmarks, is relatively modest. However, the return on investment has been substantial.

The swift five-year construction period is a testament to Korea’s cultural emphasis on speed and efficiency.

The project was designed to boost tourism, and it has done exactly that. The DDP has become a symbol of Seoul’s modernity and creativity, drawing visitors from all over the world.

The financial aspect of the DDP project is a significant factor in its story.

The project had a clear goal: to transform Seoul into a global design hub while also boosting tourism and the local economy.

The DDP has hosted numerous events, from high-profile fashion shows to tech conferences, all of which attract a global audience and generate tourism interest.

The influx of tourists and international attention has boosted the local economy, making the initial $350 million investment seem well worth it.

The success of the DDP highlights a critical lesson in architecture and urban planning as well as winning competition strategy: understanding the financial and strategic objectives behind a project is just as important as the design itself.

In the case of the DDP, the focus was less on the historical significance of the site and more on the future economic benefits.

Zaha Hadid’s design, with its futuristic and dynamic form, perfectly aligned with these objectives. The DDP stands as a testament to how a well-executed architectural project can drive economic growth and elevate a city’s global status.

It’s a reminder that in the world of architecture, money often rules, and understanding the economic and strategic goals can be the key to winning a competition.

Final Thought

Reflecting on this, I realize that winning an architecture competition, much like responding to an RFP (Request for Proposal) in the architecture industry, hinges on understanding both the explicit and implicit objectives.

For Seoul, the historical context was secondary to the vision of a future-focused design landmark.

Knowing the Korean penchant for speed and focus, it’s no surprise the competition’s leaders didn’t emphasize history.

While I can not ask Zaha Hadid, who passed away in 2016, I’m confident she understood the competition’s goals perfectly. In doing so, she created a structure that stands as a testament to Seoul’s ambitions and her architectural genius.

So, can you win an architecture competition without grasping the history of the site? Yes, as long as you grasp the vision and objectives behind the project.

Now, back to my primary focus in Seoul Trip—more Korean food!