Recently I made a suggestion to my student that surprised even me—enter an architecture design competition.

This recommendation came despite my own complicated history with competitions, which made me reflect on why I was encouraging something I had personally abandoned.

As an architect, I’m well aware of the story surrounding architecture competitions.

We’ve all read about famous architects who launched their careers by winning prestigious competitions, using that momentum to build their practices and secure future projects. It’s practically architectural tradition—win a competition, make your name, and doors will open.

But reality rarely follows such a clean storyline. My own competition experiences involved endless design iterations, starting over repeatedly when ideas failed, pulling all-nighters fueled by desperation, subsisting on cold pizza, and inevitably submitting work moments before deadlines—both as a student and later as a professional.

When I founded my architecture office a decade ago, winning competitions seemed like a viable strategy for building my practice. However, after investing some time and money (those registration fees add up) with nothing to show for it, I eventually abandoned the approach. The return on investment simply wasn’t there.

So why, despite this history, did I find myself encouraging my student to enter a competition? Seeing the student’s hesitation—which mirrored my own feelings—I began reconsidering the value of competitions beyond simply winning or losing.

Showcasing Design Depth

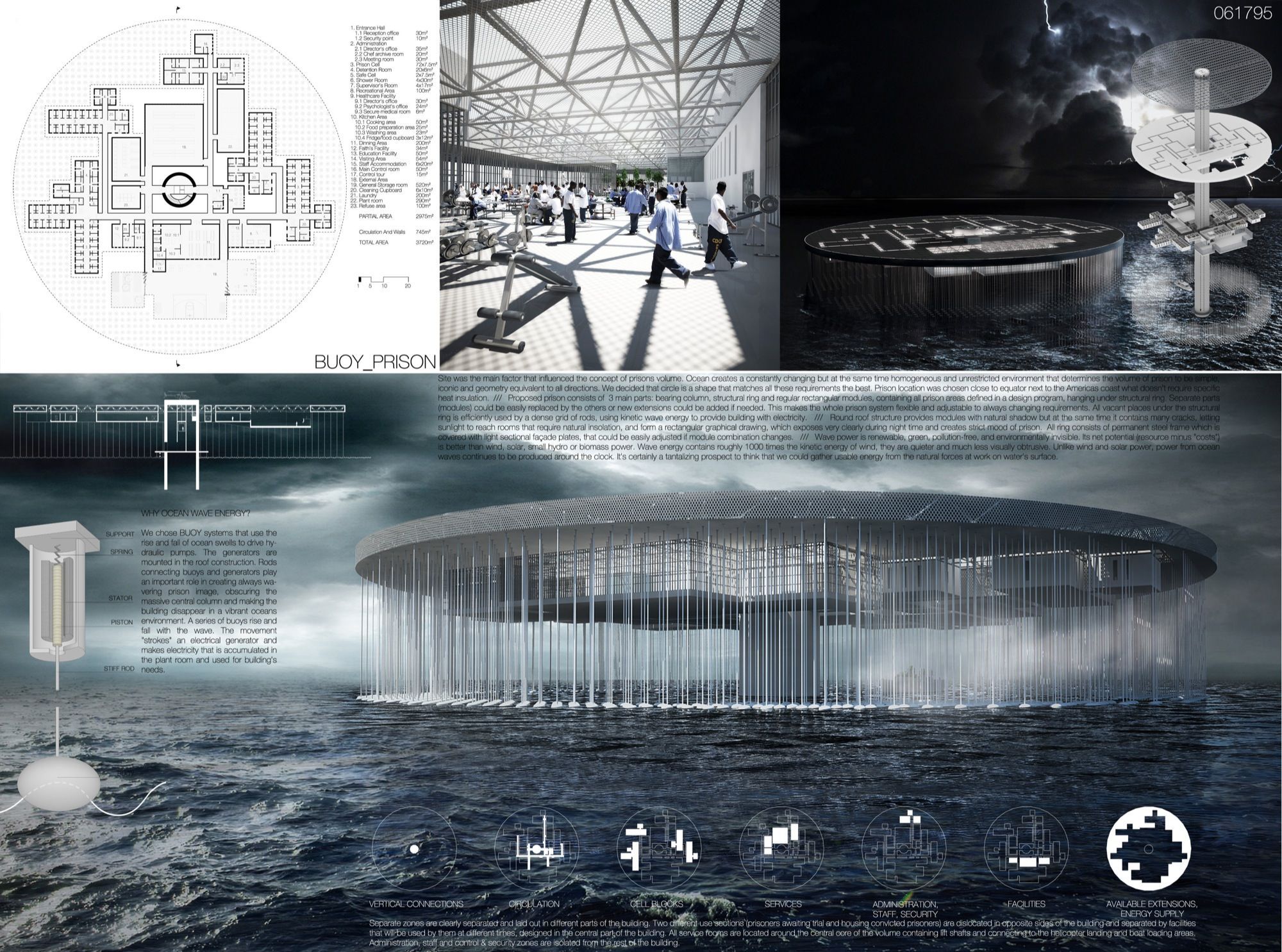

Architecture competitions are visually driven work.

Success depends on stunning renderings, meticulously crafted drawings, clear diagrams, and beautifully composed presentation panels. With numerous submissions and judges who must quickly assess each entry, having an immediate “wow factor” is essential to survive the first (or more) cuts.

I’ve reviewed many competition entries with gorgeous graphics but conceptually shallow designs.

What makes student projects different—particularly those developed over an entire semester—is their depth.

The weekly refinement through instructor feedback, desk crits, and iterative design processes produces work with substantial conceptual foundations.

For example, one of my students spent whole semester developing a community center design, beginning with intensive site analysis and community interviews. Each week she refined the spatial relationships, materiality, and environmental strategies based on our discussions.

The resulting project had a richness that couldn’t be achieved in a rushed competition timeframe.

Watching this student’s consistent progress—a commitment to refining both design concepts and graphic representation—convinced me the work deserved wider recognition. The competition would be a platform to showcase the depth that comes from a semester-long design process.

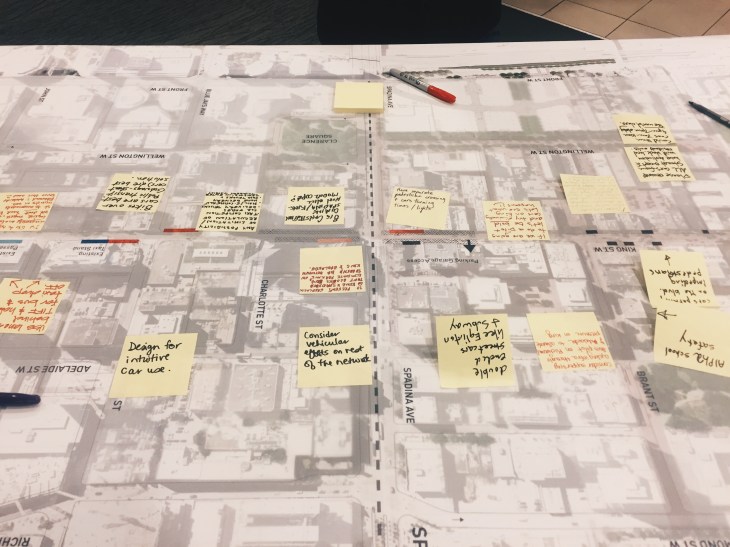

Gaining Perspective Through Comparison

Competitions offer another benefit I hadn’t previously considered: contextual feedback.

While competition results are binary (you either win or you don’t), submitting work creates an opportunity to see how your project stands among peers.

I recall a former student who entered a regional housing competition. Though she didn’t win, seeing the other entries transformed her understanding of her own work. “I realized my design solutions were innovative,” she told me, “but my presentation wasn’t communicating the social aspects clearly enough.” This realization shaped her approach to subsequent projects.

The competition transforms abstract feedback into concrete comparisons.

Instead of wondering how your work measures up, you can actually see it alongside other approaches to the same problem. This comparative knowledge is invaluable in subjective field like design.

The Possibility of Winning Remains

Of course, we can’t ignore the most obvious benefit: you might actually win.

As the saying goes, “You cannot win if you don’t play.” Design awards, monetary prizes, publication opportunities, and potentially seeing your concept built are powerful incentives.

One of my most successful former students credits his current position at a prestigious firm to winning a small sustainability competition during his final year. The recognition opened doors that might have remained closed otherwise.

When I saw hesitation on my student’s face after suggesting the competition, I shared advice my professor once gave me: “Why don’t you focus on the experience rather than the outcome?”

This perspective acknowledges the abundance of rejection in the architecture profession while finding value in the process itself.

Finding Value in the Process

The disadvantages of entering architecture competitions are well-documented: grueling hours, unpaid work, and statistically slim chances of success. Yet standing back as an instructor, watching students develop their projects over time, I’ve gained new perspective.

Competition preparation refines skills that serve students throughout their careers.

The pressure to communicate ideas clearly, to create compelling visuals, to edit designs to their essential elements—these are valuable regardless of outcome.

I’ve seen students transform their presentation abilities through competition preparation, skills that later helped them in job interviews and client meetings.

Final Thoughts: Redefining Success

My history of being the competition skeptic to cautious advocate represents a realization about architectural education.

Success isn’t always measured in awards or recognition. Sometimes the greatest value comes from the challenge itself—from pushing boundaries, meeting deadlines, and learning to present work effectively.

Architecture competitions, for all their flaws, create a framework for this growth. They push students to elevate their work beyond classroom requirements. They prepare students for the professional realities of strict deadlines, presentation standards, and yes, frequent rejection.

As I guide students through their architectural education, I’ve come to appreciate that competition participation teaches resilience.

It helps students understand that architecture is both art and communication—that brilliant ideas must be effectively conveyed to have impact.

So while I still acknowledge the long hours, emotional rollercoaster, and long odds of competitions, I’ve made peace with their place in architectural education.

Winning isn’t everything (ok, I admit, it is alot of it)—sometimes the journey of preparation, the clarity that comes from focused effort, and the perspective gained from seeing your work among peers offers rewards that transcend any official recognition.

For students willing to embrace this perspective, architecture competitions can be valuable stepping stones in their development—regardless of whether they ever stand on the winner’s podium or not:-)